There’s a lot of discussion these days about

gut health (link is external)—how a healthy gut can support overall

health,

and the ways a compromised gut may contribute to illness and disease.

We’re learning more about the complexity of the vast, dense, microbial

world of the human gut and its influence over immune health, hormone

balance,

brain function, and mental and physical equilibrium. What relationship exists between

sleep

and this microbial ecosystem within the body? Emerging science

demonstrates that there is a very real and dynamic connection between

the microbiome and sleep itself.

What is the microbiome?

The term

microbiome (link is external)

can mean a couple of different things. It is sometimes used to describe

the collection of all microbes in a particular community. In scientific

terms, the microbiome can also refer to the

genes

belonging to all the microbes living in a community. The microbiome is

often seen as a genetic counterpart to the human genome.

The genes that make up a person’s microbiome are far more numerous

than human genes themselves—there are roughly 100 times more genes in

the

human microbiome (link is external)

than in the human genome. This makes sense when you consider that there

are somewhere in the neighborhood of 100 trillion microbes living in

(and on) each of us—a combination of many different types, including

bacteria, fungi, viruses and other tiny organisms.

This vast array of microbial life lives on our skin and throughout

the body. The largest single collection of microbes resides in the

intestine—hence the attention to “gut” health. Here, trillions of

microscopic organisms live and die—and appear to exert a profound effect

on human health.

The microbiome and sleep

The human microbiota is a complicated, dynamic ecosystem within the

body. It appears to interact in some important ways with another

fundamental aspect of living—sleep. As with much about the microbiome,

there is a tremendous amount we don’t know about this interaction. That

said, there are some fascinating possible connections and shared

influences. Scientists investigating the relationship between sleep and

the microbiome are finding that this ecosystem may affect sleep and

sleep-related physiological functions in a number of ways—shifting

circadian rhythms (link is external), altering the body’s

sleep-wake cycle (link is external), and affecting

hormones that regulate sleep (link is external) and wakefulness. Our sleep, in turn, may affect the health and diversity of the human microbiome.

The microbial life within our bodies is in perpetual flux, with

microbes constantly being generated and dying. Some of this decay and

renewal naturally occurs during sleep. There’s no answer yet, however,

to the important question: What role does sleep itself play in

maintaining the health of the microbial world inside us, and which

appears to contribute so significantly to our health?

There are some important signs of a significant connection: We’ve seen research demonstrating that

circadian rhythm disruptions (link is external) can have negative effects on gut microbiota. (

More on this shortly.) There’s also evidence that the disordered breathing associated with

obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (link is external), a common

sleep disorder,

may disrupt the health of the microbiome. Scientists put mice through a

pattern of disrupted breathing that mimicked the effects of OSA, and

found that the mice that lived with periods of OSA-like breathing for

six weeks showed significant changes to the diversity and makeup of

their microbiota.

Sleep and the gut-brain connection

A significant, fast-growing body of research illustrates the far-reaching effects of the

microbiome (link is external)

over brain function and brain health—as well as the influence of the

brain over gut health and the microbiome. This “gut-brain axis” appears

likely to have a profound influence over nearly every aspect of human

health and physiological function, including

sleep (link is external).

The constant communication and interplay between the gut and the

brain has the potential to influence and intersect with sleep directly

and indirectly. Let’s take a closer look at the ways that might occur:

Mood. Studies indicate that the health and balance of the

gut microbiota (link is external)

has a significant influence over our mood and emotional equilibrium.

Disruptions and an imbalance of gut microbes have been strongly

connected to

anxiety and depression (link is external). This has potentially significant implications for sleep, as both

anxiety and

depression can trigger or exacerbate

sleep disruptions (link is external).

Stress. Research is also revealing a complicated, two-way relationship between

stress and gut health (link is external) that also may exert influence over sleep and sleep architecture. Stress is an extremely common obstacle to healthy,

sufficient sleep (link is external).

Pain. Studies link gut health to pain perception, specifically for visceral pain. An

unhealthy microbiome (link is external)

appears to increase sensitivity to this form of pain. Like so many

others, this connection travels the communication pathway between the

gut and the brain. The connection between

sleep and physical pain (link is external) or discomfort is significant—the presence of pain can make falling asleep and staying asleep much more difficult.

Hormones.

Several hormones and neurotransmitters that play important roles in

sleep also have significant influence over gut health and function. The

intestinal microbiome produces and releases many of the same

neurotransmitters (link is external)—

dopamine, serotonin, and GABA among them—that help to regulate mood, and also help to promote sleep. Also:

- Melatonin, the “darkness hormone" essential to sleep and a

healthy sleep-wake cycle, also contributes to maintaining gut health.

Deficiencies in melatonin have been linked to increased permeability of

the gut—the so-called "leaky gut" (link is external)

increasingly associated with a range of diseases. Melatonin is produced

in the gut as well as the brain, and evidence suggests that intestinal melatonin (link is external) may operate on a different cyclical rhythm than the pineal melatonin generated in the brain.

- Cortisol is another hormone critical to the human sleep-wake cycle (link is external).

Rising levels of the hormone very early in the day help to promote

alertness, focus, and energy. Cortisol levels are influenced in several

ways within gut-brain axis (link is external):

The hormone is central to the stress and inflammatory response, and

also exerts an effect on gut permeability and microbial diversity. The

changes to cortisol that occur amid the interplay of the gut and brain

are likely to have an effect on sleep.

‘Circadian rhythms’ of the gut?

There is some pretty fascinating research connecting the gut microbiome to

circadian rhythms (link is external),

the 24-hour biological rhythms that regulate our sleep and wake cycles,

in addition to many other important physiological processes. A growing

number of studies now suggest that the vast and diverse microbial

ecosystem of the gut has its own daily rhythms. These microbiome rhythms

appear to be deeply entwined with

circadian rhythms (link is external)—research suggests that both

circadian and microbial rhythms (link is external)are capable of influencing and disrupting the other, with consequences for

health and sleep (link is external).

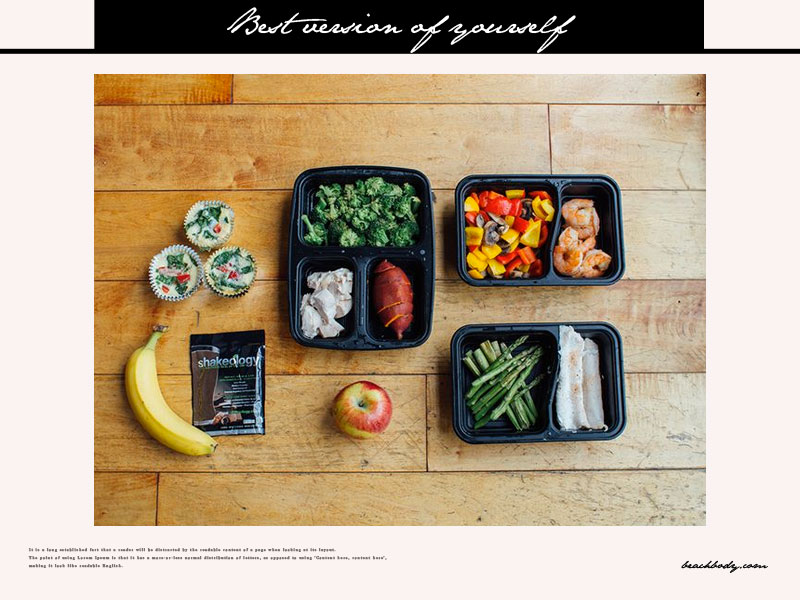

The

rhythms of gut microbes (link is external) are affected by

diet,

both the timing of our eating and the composition of the foods we

consume. A recent study found that mice eating a healthy diet generated

more beneficial gut microbes, and that the collective activity of

microbial life in the gut followed a daily—or diurnal—rhythm. That

rhythm, in turn, supported circadian rhythms in the animal. Mice fed a

high-fat, stereotypically “Western” diet, on the other hand, produced

less

optimal microbial life. The gut microbes of these mice did not adhere

to a daily rhythm themselves, and also sent signals that disrupted

circadian rhythms. These mice gained weight and became obese, while the

mice that ate healthfully did not.

Scientists bred a third group of mice without any gut microbes at

all. These mice had no signals to send from a gut microbiome. Circadian

disruption occurred in these mice—but they did not gain weight or suffer

metabolic disruption, even when fed the high-fat diet. This suggests a

couple of important conclusions. First, that microbial activity is key

to normal circadian function—and therefore to sleep. Second, that the

microbiome is a key player along with diet in the regulation of weight

and metabolism.

Circadian rhythms and microbiome: A two-way street

Research in humans has returned similar results: The human microbiome

appears to follow daily rhythms influenced by timing of eating and the

types of foods consumed, and to exert effects over circadian rhythms.

Research has also found that the relationship between these different

biological rhythms works both ways. Scientists have discovered that

disruptions to circadian rhythms (link is external)—the kind that occurs through

jet lag,

whether through actual travel or from “social” jet lag—disrupts

microbial rhythms and the health of the microbial ecosystem. People who

experience these changes to microbial rhythms as a result of circadian

disruption suffer metabolic imbalance, glucose intolerance, and weight

gain, according to research. And there’s preliminary evidence suggesting

that

gender

may play some role in the relationship of gut microbial health,

metabolism, and circadian function: a study using mice found that

females had more pronounced

microbiome rhythms (link is external) than males.

New understanding of circadian role in metabolism?

We’ve known for some time about the relationship of

sleep, circadian rhythms, and metabolic health (link is external). Disrupted sleep and misaligned circadian rhythms have been strongly tied to higher rates of

obesity and to metabolic disorders including

Type 2 diabetes. Our emerging knowledge of the microbiome and its

relationship to circadian function may in time deliver a deeper

understanding of how health is influenced by sleep and circadian

activity.

Science has really only just begun to delve into the world of the

microbiome and its relationship to sleep as well as health more broadly.

All the early signs suggest that this is a profoundly important area of

research; it will be fascinating to see where this takes us, and what

it means for sleep.

Over the past 10 years, I’ve conducted studies designed to tap the practical wisdom

for living of the oldest Americans. Using a nationally representative

survey and in-depth interviews, I invited older people (mostly age 70

and above) to tell me what younger people should do—and not do—to live

happier, more fulfilling lives. I've especially loved it when the elders

have been definitive, as it was when we asked over 1,200 elders what

they would recommend to younger people looking for ways to make the most

of their lives. Many focused on this single action:

Over the past 10 years, I’ve conducted studies designed to tap the practical wisdom

for living of the oldest Americans. Using a nationally representative

survey and in-depth interviews, I invited older people (mostly age 70

and above) to tell me what younger people should do—and not do—to live

happier, more fulfilling lives. I've especially loved it when the elders

have been definitive, as it was when we asked over 1,200 elders what

they would recommend to younger people looking for ways to make the most

of their lives. Many focused on this single action:

There’s a lot of discussion these days about

There’s a lot of discussion these days about

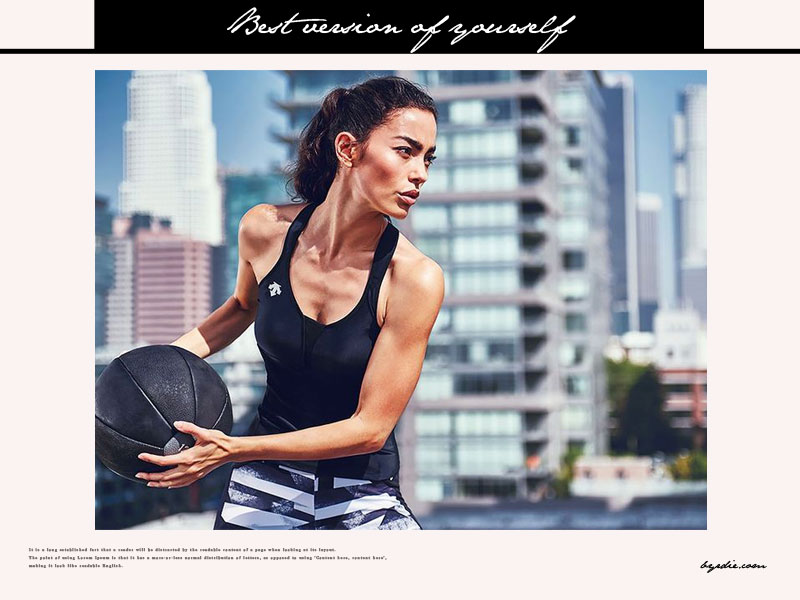

It’s well established that physical activity—especially aerobic exercise like biking or running—helps people to sleep better.

It’s well established that physical activity—especially aerobic exercise like biking or running—helps people to sleep better.