New research into our 'creepiness detector' explains a lot.

"That guy is so creepy," we occasionally say about other people. But

what does that really mean and why do we say it? Our “creepy” reaction

is both unpleasant and confusing, and according to one study (Leander,

et al, 2012), it may even be accompanied by physical symptoms such as

feeling cold or chilly. Following casual conversation with colleagues

about the psychology underlying creepiness, I decided explore what's

been studied about the phenomenon. Given how frequently creepiness is

discussed in everyday life, I was amazed that no one had yet studied it

in a scientific way. The little bit of research that was at all relevant

focused on how we respond to things such as weird nonverbal behaviors,

and being socially excluded. These studies did not use the word

creepiness, but their results implied that our “creepiness detector” may in fact be a defense against some sort of threat.

Creepiness may be related to the “agency-detection” mechanisms

proposed by evolutionary psychologists. These mechanisms evolved to

protect us from harm at the hands of predators and enemies. If you are

walking down a dark city street and hear the sound of something moving

in a dark alley, you will respond with a heightened level of arousal and

sharply focused attention and behave as if there is a willful “agent”

present who is about to do you harm. If it turns out to be just a gust

of wind or a stray cat, you lost little by over-reacting, but if you

failed to activate the alarm response and a true threat was present, the

cost of your miscalculation could be high.

We evolved to err on the side of detecting threats in such ambiguous situations.

What, then, does our creepiness detector warn us about? It cannot

just be a clear warning of physical or social harm. A mugger who points a

gun in your face and demands money is terrifying. A rival who threatens

to destroy your reputation by revealing secret information about you

fills you with dread. Most of us would not use the word “creepy” to

refer to either of these situations, yet in both cases there is no

ambiguity about the presence of threat. I believe that creepiness is

anxiety aroused by the

ambiguity of whether there is something to

fear, and/or by the ambiguity of the precise

nature of the threat—sexual, physical violence, or contamination, for example—that might be present.

Only when we are confronted with

uncertainty about threat do we get “creeped out."

Our

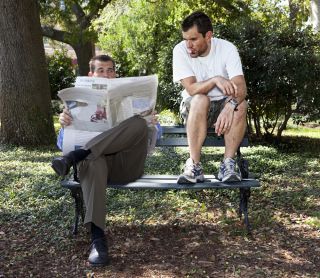

uncertainty paralyzes us about how to respond. For example, it would be

considered rude, and strange, to run away in the middle of a

conversation with someone is sending out a creepy vibe but is actually

harmless; it could be perilous to ignore your

intuition

and engage with that individual if he is dangerous. This ambivalence

may leave you frozen in place, wallowing in creepiness. Yet this

reaction could still be adaptive if it helps you maintain vigilance

during such periods of uncertainty and manage the balance between

self-preservation and social obligation.

I began to identify the components of creepiness. Since there was no

previous body of research to build upon, I decided to pursue this

question in a study with one of my students, Sara Koehnke. Our study was

unavoidably exploratory in nature, but we had a few hypotheses:

- If creepiness communicates potential threat, males should be

more likely to be perceived as creepy than females, since males are

generally more violent and physically threatening to more people (see

McAndrew, 2009).

- Related to the first prediction, females should be more likely than males to perceive some sort of sexual threat from a "creepy" person.

- Occupations that signal a fascination with threatening stimuli, such as death or "non-normative" sex, may attract individuals that would be comfortable in such a work environment. Hence, some occupations should be perceived as creepier than other occupations.

- Since we hypothesize that creepiness is a function of uncertainty

about threat, non-normative nonverbal behaviors and behaviors or

characteristics associated with unpredictability will be positively

associated with perceptions of creepiness.

We recruited volunteers to fill out an online survey through

Facebook,

and ended up with a sample of 1,341 individuals (1,029 females, 312

males) ranging in age from 18 to 77 with a mean age of 28.97 (SD =

11.34). In the first section of the survey, our participants rated the

likelihood that a hypothetical “creepy person” would exhibit 44

different behaviors, such as unusual patterns of eye contact or physical

characteristics like visible tattoos. In the second section of the

survey, participants rated the creepiness of 21 different occupations,

and in the third section, they simply listed two hobbies that they

thought were creepy. In the final section, participants expressed their

level of agreement with 15 statements about the nature of creepy people.

Our study confirmed the following:

- Perceived creepy people are more likely to be males than females.

- Females are more likely to perceive sexual threat from creepy people.

- Occupations do differ in level of perceived

creepiness. Clowns, taxidermists, sex-shop owners, and funeral directors

were at the top of the list.

- Unpredictability is an important component of perceived creepiness.

- A variety of non-normative physical characteristics and nonverbal behaviors contribute to perceptions of creepiness.

- Participants did not believe that most creepy people realize they

are creepy, nor did they believe that creepy people necessarily have bad

intentions. However, they also believed that creepy people could not

change.

- The most frequently mentioned creepy hobbies involved collecting

things, such as dolls, insects, or body parts such as teeth. Bones or

fingernails were considered especially creepy; the second most

frequently mentioned creepy hobby involved some variation of "watching,"

such as taking pictures of people, watching children, pornography, and even bird watching.

The results are consistent with the idea that creepiness is a

response to the ambiguity of threat. Non-normative non-verbal

and emotional behaviors, unusual physical characteristics and hobbies,

or suspect occupations set off our “creepiness detector." Men are

considered more likely to be creepy by males and females alike; women

are more likely to perceive sexual threat from creepy people.

We have not yet published our results, but we have presented at

several conferences. And I plan to expand my study from creepy people to

creepy places: We become uneasy, for example, in environments that are

dark and/or offer a lot of hiding places for potential predators and

also lack clear, unobstructed views of the landscape. These

environmental qualities have been called “prospect” and "refuge” by

British geographer Jay Appleton. Fear of

crime and

a pervasive sense of unease are experienced in environments with less

than optimal combinations of prospect and refuge. In creepy places as

with creepy people, I expect to find that it is not the clear presence

of danger that creeps us out, but rather the

uncertainty of whether danger is present or not.

At any moment, you can send people positive vibes or negative vibes.

You can hug, connecting with people in a positive way, physically and

also verbally. Or, you can push people away or knock them down, again either physically or via verbal complaints, disagreement, or blame. (link is external)

At any moment, you can send people positive vibes or negative vibes.

You can hug, connecting with people in a positive way, physically and

also verbally. Or, you can push people away or knock them down, again either physically or via verbal complaints, disagreement, or blame. (link is external) The debut of the Remington typewriter in 1873 radically altered how

people could communicate thoughts. Since then, we have debated whether

handwriting was still necessary. Today, kids tap keyboards and phones

but rarely, if ever, write by hand even a thank-you card.

The debut of the Remington typewriter in 1873 radically altered how

people could communicate thoughts. Since then, we have debated whether

handwriting was still necessary. Today, kids tap keyboards and phones

but rarely, if ever, write by hand even a thank-you card. "That guy is so creepy," we occasionally say about other people. But

what does that really mean and why do we say it? Our “creepy” reaction

is both unpleasant and confusing, and according to one study (Leander,

et al, 2012), it may even be accompanied by physical symptoms such as

feeling cold or chilly. Following casual conversation with colleagues

about the psychology underlying creepiness, I decided explore what's

been studied about the phenomenon. Given how frequently creepiness is

discussed in everyday life, I was amazed that no one had yet studied it

in a scientific way. The little bit of research that was at all relevant

focused on how we respond to things such as weird nonverbal behaviors,

and being socially excluded. These studies did not use the word creepiness, but their results implied that our “creepiness detector” may in fact be a defense against some sort of threat.

"That guy is so creepy," we occasionally say about other people. But

what does that really mean and why do we say it? Our “creepy” reaction

is both unpleasant and confusing, and according to one study (Leander,

et al, 2012), it may even be accompanied by physical symptoms such as

feeling cold or chilly. Following casual conversation with colleagues

about the psychology underlying creepiness, I decided explore what's

been studied about the phenomenon. Given how frequently creepiness is

discussed in everyday life, I was amazed that no one had yet studied it

in a scientific way. The little bit of research that was at all relevant

focused on how we respond to things such as weird nonverbal behaviors,

and being socially excluded. These studies did not use the word creepiness, but their results implied that our “creepiness detector” may in fact be a defense against some sort of threat. Everyone experiences a bad mood or a case of the blues sometimes. If

you wake up feeling down, or catch yourself slipping into a state of

melancholy throughout the day, remember that we each have

ultimate control over our moods. Regardless of what is going on around

you, these 4 steps can quickly help lift your spirits:

Everyone experiences a bad mood or a case of the blues sometimes. If

you wake up feeling down, or catch yourself slipping into a state of

melancholy throughout the day, remember that we each have

ultimate control over our moods. Regardless of what is going on around

you, these 4 steps can quickly help lift your spirits: Fear is a basic human emotion. It was wired into our systems for a

beneficial purpose—to signal us in times of danger and prepare us

physically so we could accomplish what is necessary for survival.

Fear is a basic human emotion. It was wired into our systems for a

beneficial purpose—to signal us in times of danger and prepare us

physically so we could accomplish what is necessary for survival. We humans have a compelling need to be social. We need close

relationships in our lives and when we feel disconnected or isolated

from the people we love, the result is the troubling state we call loneliness. For some, loneliness is an occasional annoyance, but for others, it can become a painful, even debilitating condition.

We humans have a compelling need to be social. We need close

relationships in our lives and when we feel disconnected or isolated

from the people we love, the result is the troubling state we call loneliness. For some, loneliness is an occasional annoyance, but for others, it can become a painful, even debilitating condition.